Wu Chinese

| Wu Chinese | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 吳語 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 吴语 | ||||||||||

| Wu | Ng nyiu (colloquial) or Ghu nyiu (literary) | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Wu | ||

|---|---|---|

| 吳語/吴语 |

||

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Shanghai; most of Zhejiang province; southern Jiangsu province; Xuancheng prefecture-level city of Anhui province; Shangrao County, Guangfeng County and Yushan County, Jiangxi province; Pucheng County, Fujian province; North Point, Hong Kong | |

| Total speakers | ~90 million | |

| Ranking | 10 [2] | |

| Language family | Sino-Tibetan

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | zh | |

| ISO 639-2 | chi (B) | zho (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | wuu | |

| Linguasphere | ||

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

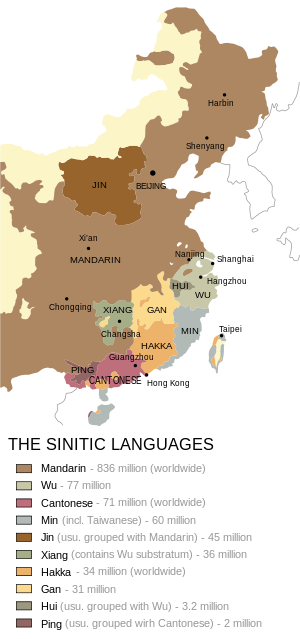

Wú (simplified Chinese: 吴语; traditional Chinese: 吳語; pinyin: Wú yǔ; Wade–Giles: Ng nyiu (colloquial) or Ghu nyiu (literary) is one of the major divisions of the Chinese language. It is spoken in most of Zhejiang province, the municipality of Shanghai, southern Jiangsu province, as well as smaller parts of Anhui, Jiangxi, and Fujian provinces.

Major Wu dialects include those of Shanghai, Suzhou, Wenzhou, Hangzhou, Shaoxing, Jinhua, Yongkang, and Quzhou. The traditional prestige dialect of Wu is the Suzhou dialect, though due to its large population, Shanghainese is today sometimes considered the prestige dialect. Note that Wu is the term used by scholars and an endonym by many of its speakers is 'Jiangnan speech' (江南話) or 'Jiangsu-Zhejiang speech', or 'Jiangzhe speech' (江浙話). Another term for Wu Chinese, less used often is 'Wuyue speech' (吳越語), often a reference to the two kingdoms of Wu and Yue, and/or to the kingdom of Wuyue.

Among speakers of other Chinese languages, Wu is often subjectively judged to be soft, light, and flowing. There is even a special term used to describe these qualities of Wu speech (simplified Chinese: 吴侬软语; traditional Chinese: 吳儂軟語; pinyin: wúnóngruǎnyǔ). The actual source of this impression is harder to place. It is likely a combination of many factors. Among speakers of Wu, for example, Shanghainese is considered softer and mellower than the variant spoken in Ningbo, although some Wu speakers still insist that old standard Suzhou dialect is more pleasant and beautiful than the dialects of Shanghai and Ningbo.

Like other varieties of Chinese, there is disagreement as to whether Wu should be considered a language of its own or as a dialect of a Chinese language. (See Varieties of Chinese for the issues surrounding this dispute.) By the standard of mutual intelligibility, Wu is a language separate from Mandarin, Cantonese, and other varieties of Chinese. However, it does not have a standardized form as Mandarin does; it is seldom written, as Wu speakers write in Vernacular Chinese, with grammar and vocabulary centred on Standard Mandarin (with a few allowances for regional variation) rather than on Wu.

Contents |

History

The modern Wu language can be traced back to the ancient Wu and Yue peoples centred around what is now southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang. The Japanese Go-on (呉音 goon) pronunciation of Chinese characters (obtained from the Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms period) is from the same region of China where Wu is spoken today. Wu Chinese itself has a 2,600 year old history, dating back to the Spring and Autumn Period.

Origins

Like most other branches of Chinese, Wu descends from Middle Chinese. Although Wu represents the earliest split from the rest of these branches, and thus keeps many ancient characteristics, it was influenced by northern Chinese (Mandarin) throughout its development. This was due to its geographical closeness to North China and also to the high rate of education in this region. During the time between Ming Dynasty and early Republican era, the main characteristics of modern Wu were formed. The Suzhou dialect became the most influential, and many dialectologists use it in citing examples of Wu.

After the Taiping Rebellion at the end of the Qing dynasty, in which the Wu-speaking region was devastated by war, Shanghai was inundated with migrants from other parts of the Wu-speaking area. This greatly affected the dialect of Shanghai, bringing, for example, influence from the Ningbo dialect to a dialect which, at least within the walled city of Shanghai, was almost identical to the Suzhou dialect. As a result of the population boom, in the first half of the 20th century, Shanghainese became almost a regional lingua franca within the region, to some extent eclipsing the status of the Suzhou dialect.

Post-1949

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the strong promotion of Mandarin in the Wu-speaking region influenced the development of the language. Wu was gradually excluded from most modern media and schools. Public organisations were required to use Mandarin. With the influx of a migrant non Wu-speaking population and the near total conversion of public media and organizations to the exclusive use of Mandarin, as well as the radical Mandarin promotion measures, the development of the Wu dialects was greatly hampered. It became common in the region to encounter children who grew up with Mandarin as their mother tongue, with little or no fluency in Wu at all.

Many people have noticed this trend and thus call for the protection of this language. More and more TV programs are appearing in Wu, although they are mostly comedies rather than formal programs.

Roughly speaking, modern Wu is a leftover of the Chinese dialects – see language tree starting from 1500 BC with Wu's position relative to other dialects.

Varieties

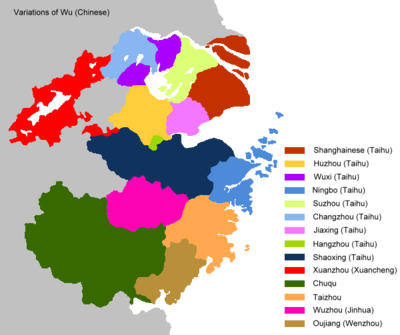

Many Wu dialects are diverse and not mutually intelligible with each other. However, all Wu dialects including Oujiang can understand the Taihu dialect, while Taihu speakers find the other dialects unintelligible or intelligible only to a small extent.

According to Yan (2006), Wu is divided into six dialect areas:

- Taihu (i.e., Lake Tai region): Spoken over much of southern part of Jiangsu province, including Suzhou, Wuxi, Changzhou, the southern part of Nantong, Jingjiang and Danyang; the municipality of Shanghai; and the northern part of Zhejiang province, including Hangzhou, Shaoxing, Ningbo, Huzhou, and Jiaxing. This group makes up the largest population among all Wu speakers. The subdialects of this region are, in a large degree, mutually intelligible among each other.

- Shanghainese

- Suzhou dialect

- Hangzhou dialect

- Ningbo dialect

- Wuxi dialect

- Changzhou dialect

- Jiangyin dialect

- Qihai dialect

- Jinxiang dialect

- Taizhou (台州): Spoken in and around Taizhou, Zhejiang province. Taizhou Wu is among the southern dialects the closest to Taihu Wu, also known as North Wu, and can communicate with speakers of Taihu Wu.

- Taizhou dialect

- Oujiang (甌江/瓯江)/Dong'ou (東甌片/东瓯片): Spoken in and around Wenzhou, Zhejiang province. This dialect is the most distinctive and mutually unintelligible among all the Wu dialects. Some dialectologists even treated it as a dialect separate from the rest of Wu dialect.

- Wenzhounese

- Wuzhou (婺州): Spoken in and around Jinhua, Zhejiang province. Like Taizhou Wu dialect, it is mutually intelligible with Taihu Wu dialect at least to some degree.

- Chuqu (處衢/处衢): Spoken in and around Lishui and Quzhou in Zhejiang as well as in Shangrao County and Yushan County in Jiangxi province.

- Quzhou dialect

- Jiangshan dialect

- Qingtian dialect

- Xuanzhou (宣州): Spoken in and around Xuancheng, Anhui province. This part of Wu is becoming less spoken since the campaign started by Taiping Rebellion and is being slowly replaced by the immigrants' mandarin dialect from the north of Yangtse river.

Phonology

According to Yan (2006), the Wu dialects are notable among Chinese languages in having kept the "muddy" (voiced, or more precisely slack voiced) plosives and fricatives of Middle Chinese, such as /b̥/, /d̥/, /ɡ̊/, /z̥/, /v̥/, etc., thus maintaining the three-way contrast of Middle Chinese stop consonants and affricates, /p pʰ b̥/, /tɕ tɕʰ d̥ʑ̊/, etc. Because Wu dialects never lost these voiced obstruents, the tone split of Middle Chinese is still allophonic, and most dialects have three syllabic tones (though counted as eight in traditional descriptions). In Shanghai, these are reduced to two word tones.

See Suzhou dialect, Hangzhou dialect, Changzhou dialect, Shanghainese, Quzhou dialect, Jiangshan dialect and Wenzhounese for examples of Wu phonology.

Wu Chinese has preserved the three-way contrast system. For example:

- 「凍」、「痛」、「洞」 - [t], [tʰ], [d]

Where as in Mandarin, the initial of 「洞」 has changed to [t].

Literary and Vernacular pronunciations in Shanghai dialect

「家」 (house) [ʨia52]L/[ka52]V

「顏」 (face) [ɦiɪ113]L/[ŋʱɛ113]V

「櫻」 (cherry) [ʔiŋ52]L/[ʔã52]V

「孝」 (filial piety) [ɕiɔ335]L/[hɔ335]V

「學」 [ʱjaʔ2]L/[ʱoʔ2]V

「物」 [vəʔ2]L/[mʱəʔ2]V

「網」 (web) [ʱwɑŋ113]L/[mʱɑŋ113]V

「鳳」 (male phoenix) [voŋ113]L/[boŋ113]V

「肥」 (fat) [vi113]L/[bi113]V

「日」 (sun) [zəʔ2]L/[ɳʱiɪʔ2]V

「人」 (person) [zən113]L/[ɳʱin113]V

「鳥」 (bird) [ʔɳiɔ335]L/[tiɔ335]V

Grammar

The Wu pronoun system is complex when it comes to personal and demonstrative pronouns. For example, the first person plural pronoun differs when it is inclusive (including the hearer) and when it is exclusive (excluding the hearer, such as "me and him/her/them not you"). Wu employs six demonstratives, three of which are used to refer to close objects, and three of which are used for farther objects.

In terms of word order, Wu uses SVO (like Mandarin), but unlike Mandarin, it also has a high occurrence of SOV and in some cases OSV[1][2]

In terms of phonology, tone sandhi is extremely complex, and helps parse multisyllabic words and idiomatic phrases. In some cases, indirect objects are distinguished from direct objects by a voiced/voiceless distinction.

In most cases, classifiers take the place of genitive particles and articles — a quality shared with Cantonese — as shown by the below Wu Chinese examples:

- *本書交關好看。 *我支筆 *渠碗粥

These examples in Wu Chinese are the equivalents of 書很好看, 我的筆, and 他的粥 in Mandarin Chinese.

The respective glosses in English are roughly: volume (this) book rather than this book, my stick of pen rather than my pen, and his bowl of congee rather than his congee.

Examples

Quzhou dialect

- 你 我 個 朋友 啘。

[ni ŋu kəʔ põjɤ ue]

Literal meaning:(2nd person singular) (1st person singular) (genitive) (friend) (particle)

Meaning: You are my friend. Compare with Japanese: "あなたは私の友達だよ.", or "anata wa watashi no tomodachi dayo"。In this case, "啘", resembles Japanese "だよ".

- 渠(其) 你 老師 啘,要 尊重 人家。

[ɡi ɳi lɔsʐ ue, iɔ tseɳd͡ʒõ ninkɒ]

Literal meaning:(3rd person singular) (2nd person singular) (teacher) (particle), (have) (respect) (other)

Meaning: He is your teacher, and you have to respect him.

- 鉛筆 借 我 支 好伐?

[kæpiəʔ t͡ʃiɒ t͡sʐ ŋu xɔfɐ̞ʔ]

Literal meaning: (pencil) (borrow) (1st person singular) (measure word for pencil)(interrogative)

Meaning: Can I borrow a pencil?

- 飯 再 喫 碗 添,多 吃 些兒 啊。

[væ t͡se t͡ɕʰiəʔ uə tʰie, tu t͡ɕʰiəʔ ʃin o]

Literal meaning: (rice/meal) (again) (eat) (bowl) (particle?), (more) (eat) (more+) (particle)

Meaning: If you want to eat more, then eat more if you'd like.

- 感冒藥 喫嘞 朆 你,覅 記弗着 掉 唻!

[kəmɔjɐ̞ʔ t͡ɕʰiəʔləʔ vən ɳi, fiɔ t͡ɕʰifəʔt͡ʃɐ̞ʔ tɔ le]

Literal meaning: (cold medicine) (taking/eating) (interrogative) (2nd person singular), (negative) (verb-remember/negative) (particle) (imperative)

Meaning: Have you taken your cold medicine yet? Don't forget to take it!

Shanghainese

- 其 勒 門口頭 立 勒許。

[ɦi le məŋ.kʰɤɯ.dɤɯ lɪʔ lɐˑ.he]

He was standing at the door.

Gloss: Third-person (past participle) doorway(particle) stand (existed)

Vocabulary

Like other varieties of Southern Chinese, Wu Chinese retains some archaic vocabulary from Classical Chinese, Middle Chinese, and Old Chinese.

Examples

Mandarin equivalents and their pronunciation on Wu Chinese are in parentheses. All IPA transcriptions and examples listed below are from Shanghainese.

「許」(那) [he] (na) (particle)

「汏」(洗) [da] (si) to wash

「囥」(藏) [kɔŋ] (zɔŋ) to hide something

「隑」(斜靠) [ɡe] (ʑ̊ia kʰɔ) to lean

「廿」(二十) [ne] (əl sɐʔ) twenty (The Mandarin equivalent, 二十, is also used to a lesser extent, mostly in its literary pronunciation.)

「弗」/「勿」(不) [və] (pʰə) no, not

「立」(站) [liɪʔ] (ze) to stand

「囡」 [nø] child, whelp (It is pronounced as nān in Mandarin.)

「睏」(睡) [kʰwəŋ] (zø) to sleep

「尋」(找) [ʑ̊iɲ] (tsɔ) to find

「戇」 [ɡɔɲ] foolish, stupid. (It is a cognate of the Min word 歞, which is ngâung [ŋɑuŋ˨˦˨] in Fuzhou dialect and gōng [koŋ˧] in Min Nan.)

「揎」 [ɕyø] to strike (a person)

「逐」(追) [zoʔ] or [tsoʔ] (tsø) to chase

「焐」 [u] to make warm, to warm up (ex. 焐焐熱)

「肯」 [kʰəɲ] to permit, to allow

「事體」 [z̥z tʰi] thing (business, affair, matter)

「歡喜」 [hø ɕi] to like, to be keen on something, to be fond of, to love

「物事」 [məʔ z̥z̩] things (more specifically, material things)

In Wu dialects, the morphology of the words are similar, but the characters are switched around. Not all Wu Chinese words exhibit this phenomenon, only some words in some dialects.

To the left are words in Quzhou dialect, to the right are their Mandarin equivalents.

歡喜-huos-喜歡

鬧熱-nawnieh-熱鬧

人客-ninchiah-客人

火著-hujah-著火

聯對-lietei-對聯

項頸-ngaoncin-頸項

背脊-peicieh-脊背

牆圍-zhianwei-圍牆

Note that this would be only for Quzhou dialect, Shanghainese only has 歡喜, 鬧熱, and 背脊, but 圍牆. Though 人客 and 客人 are both used in Shanghainese.

Preference of archaic words

Like other varieties of Southern Chinese, Wu prefers more archaic words to 'to speak'. For example:

In most Wu dialects, with the exception of Hangzhou dialect, 講 [ɡɔŋ] is preferred when referring to speaking rather than the Mandarin shuō 說 [sɐʔ]. In Guangfeng and Yushan counties of Jiangxi province, 曰 [je] is generally preferred over 說. In Shangrao county of Jiangxi province, 話 [wa] is preferred over 說.

Colloquialisms

In Wu Chinese, there are colloquialisms that are traced back to ancestral Chinese varieties, such as Middle or Old Chinese. Many of those colloquialisms are cognates of other words found in other modern southern Chinese dialects, such as Gan, Xiang, or Min.

Mandarin equivalents and their pronunciation on Wu Chinese are in parentheses. All IPA transcriptions and examples listed below are from Shanghainese.

「鑊子」 (鍋子) [ɦɔ zɨ] (ɡu zɨ) wok, cooking pot. The Mandarin equivalent term is also used, but both of them are synonyms and are thus interchangeable.

「結棍」(厲害) [tɕiɪʔ kuɛɲ] (li ɦe) formidable. It literally means to gather and bundle up sticks.

「戇大」 [ɡɔɲ d̥u] idiot, fool

「衣裳」 (衣服) [i z̥ã] (i v̥oʔ) clothing. Found in other Chinese dialects. It is a reference to traditional Han Chinese clothing, where it consists of the upper garments 「衣」 and the lower garments 「裳」.

Erhua

In Taihu Wu Chinese, an Erhua-like process exists in some nouns as diminutives, but not as rhotic sounds, but nasal sounds.

- 麻雀 (mu tsiah) --> 麻雀儿/麻将 (mu tsiang)

- 耳括 (ni kuah) --> 耳括兒/耳光 (ni kuang)

See also

- Wu (region)

- Jiangnan

- Wu-speaking peoples

- Wuyue

- List of Chinese dialects

References

- Yan, M.M. (2006). Introduction to Chinese Dialectology. Munich: Lincom Europa

External links

Resources on Wu dialects

- glossika.com

- Shanghainese Wu Dictionary – Search in Mandarin, IPA, or (English)

- Classification of Wu Dialects – By James Campbell

- Tones in Wu Dialects – Compiled by James Campbell

- Linguistic Forum of Wu Chinese(simplified Chinese: 吴语论坛) –

A BBS set up in 2004, in which topics such as phonology, grammar, orthography and romanization of Wu Chinese are widely talked about. The cultural and linguistic diversity within China is also a significant concerning of this forum.

- (in simplified Chinese)

- “The elegant language in Jiangnan area” (simplified Chinese: 江南雅音话吴语) – Excellent reference on Wu Chinese, including tones of the sub-dialects.

- Wu Chinese Online Association – Aimed at modernization of Wu Chinese, including basics of Wu, Wu romanization scheme, pronunciation dictionaries of different dialects, Wu input method development, Wu research literatures, written Wu experiment, Wu orthography, a discussion forum etc.

Articles

- Globalization, National Culture and the Search for Identity: A Chinese Dilemma (1st Quarter of 2006, Media Development) – A comprehensive article, written by Wu Mei and Guo Zhenzhi of World Association for Christian Communication, related to the struggle for national cultural unity by current Chinese Communist national government while desperately fighting for preservation on Chinese regional cultures that have been the precious roots of all Han Chinese people (including Hangzhou Wu dialect). Excellent for anyone doing research on Chinese language linguistic, anthropology on Chinese culture, international business, foreign languages, global studies, and translation/interpretation.

- Modernisation a Threat to Dialects in China – An excellent article originally from Straits Times Interactive through YTL Community website, it provides an insight of Chinese dialects, both major and minor, losing their speakers to Standard Mandarin due to greater mobility and interaction. Excellent for anyone doing research on Chinese language linguistic, anthropology on Chinese culture, international business, foreign languages, global studies, and translation/interpretation.

- Middlebury Expands Study Abroad Horizons – An excellent article including a section on future exchange programs in learning Chinese language in Hangzhou (plus colorful, positive impression on the Hangzhou dialect, too). Requires registration of online account before viewing.

- Mind your language (from The Standard, Hong Kong) – This newspaper article provides a deep insight on the danger of decline in the usage of dialects, including Wu dialects, other than the rising star of Standard Mandarin. It also mentions an exception where some grassroots’ organizations and, sometimes, larger institutions, are the force behind the preservation of their dialects. Another excellent article for research on Chinese language linguistic, anthropology on Chinese culture, international business, foreign languages, global studies, and translation/interpretation.

- China: Dialect use on TV worries Beijing (originally from Straits Times Interactive, Singapore and posted on AsiaMedia Media News Daily from UCLA) – Article on the use of dialects other than standard Mandarin in China where strict media censorship is high.

- Standard or Local Chinese – TV Programs in Dialect (from Radio86.co.uk) – Another article on the use of dialects other than standard Mandarin in China.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||